How (and why) a self-taught cheesemaker built the first buffalo dairy farm in Laos

And a Chinese New Year greeting from a mystical mermaid

Hello and welcome to the Foolish Careers newsletter.

Have you ever been told: “You should get a more sensible career"? I’m Timi, and each week we interview a storyteller, artist or creative entrepreneur in Asia who ignored this advice to pursue a creative career. They show us how they paved their own path and dealt with unmitigated failures on their way to building a unique and singular foolish career.

The goal with each story: zero generic fluff.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, you have great timing! This is only Issue #3 and I’d love for you to be an early reader. Sign up, it’s free.👇

Greetings for the Year of the Metal Ox, and/or Valentine’s Day.

My email software is warning me that this email is near the length where Gmail cuts it off. I do worry they’re long, but having the full story in the email seems convenient for most people. What do you think?

👍 I'm fine with it. ~ 👎 Too long.

~Timi

INTERVIEW: How (and why) a self-taught cheesemaker built the first buffalo dairy farm in Laos

What if you had to explain the concept of a gallery, then build one, before you could present your art? What if a creator had to build YouTube or TikTok before they could produce their first video? 99.999999% of us would never get started.

And what if you craved cheese while living in the poorest country in Southeast Asia, where milk isn’t part of the diet and farmers didn’t know they could milk their buffalo?

If you’re the founders of Laos Buffalo Dairy, you do it all from scratch: build the dairy, convince farmers to rent you their buffalo, grow the grass the buffalo was going to eat, set up the breeding program to improve genetics, import the equipment. And of course, make the cheese -- and yogurt and ice cream and cheesecake.

“We wanted a midlife crisis with a purpose, not a Porsche,” says cofounder Rachel Elman O’Shea. “The Porsche would’ve been cheaper.”

Rachel is a trained chef. With her co-founder Susie Martin, a seasoned corporate executive, they decided to deal with their midlife crises by moving from Singapore to Luang Prabang, the Lao city known for its monks and languid life along the Mekong. The plan was to build a hotel, sell it, then figure out “the cheese thing” afterward.

But a farmer was willing to lend them his buffalo for the cheese experiment. Before they knew it, they were learning to milk buffalo and trying (and failing) to make buffalo mozzarella.

Listen to Rachel tell her story 🎧

Lessons for building a creative venture from scratch

1. Identify your riskiest assumptions, and validate those first.

Will the Lao swamp buffalo give milk? And can the milk be made into mozzarella? It’s easy to assume the answer to both questions is yes, but the local breed had subpar genetics so nobody knew what to expect. Also, Rachel had never made cheese before. And the founders were going to sell their homes to fund this new business, so it had to be de-risked.

By sheer coincidence, a tourist staying at their guesthouse had 25 years of dairy experience. She wrote down directions for how to milk a buffalo, and armed with a Lao translation, the founders walked up to their first herd, not knowing how the animals would respond.

As it turned out, buffalo are like big puppy dogs. The humans were quickly surrounded by buffalo calmly looking them up and down. With the help of YouTube videos, they worked with the farmer, Mr. Eh, and his wife, on milking them. They got very little milk, but it was a start, and a six-week trial was underway.

“Every three to four days, I would have enough milk to make cheese, and cry,” Rachel says. “There was a lot of crying going on during this time because you cannot find buffalo milk cheese recipes online. Very few people make it, and no one shares the recipes. I had to use cow milk recipes and the compositions of the milk were not the same. Not being a chemist, I was just guessing.”

With the six-week deadline looming, Rachel emailed 15 dairies worldwide. “I said, ‘We're this tiny little place in the middle of nowhere. We're trying to help the local community by giving farmers an extra income stream. And in the process, I want cheese. Please help me with the recipe. It's not working.’”

She received just one response, from a cheesemaker at Shaw River Dairy in Australia, who shared her recipe with a warning that the different fat levels would change how the ingredients react. This information was enough for Rachel. “I started with her recipe and it got me much closer and I adjusted again. And finally, we had a perfect little ball of mozzarella.”

2. Identify and work with your high-expectation customers first.

What is a high-expectation customer? This term was coined by Julie Supan, a branding expert who crafted the customer positioning for YouTube and Airbnb in their earliest days.

“The high-expectation customer (HXC) is the most discerning person within your target demographic. It’s someone who will acknowledge—and enjoy—your product or service for its greatest benefit. The HXC needs to be a person who others aspire to emulate because they see them as clever, judicious and insightful. If your product exceeds their expectations, it can meet everyone else’s.”

Rachel’s HXC for mozzarella was, without a doubt, Somsack Sengta, the Lao-born, Swiss-trained chef and owner of Blue Lagoon Restaurant, a Luang Prabang institution.

For the Italian mozzarella he used in his restaurant, Somsack was already resorting to hand-carrying the product from Thailand or Singapore, an expensive and time-consuming arrangement, just to avoid sub-optimal shipping conditions. To go from that to a supplier up the road? He gave Rachel feedback for a year, then finally placed his first order.

On the supply side, they needed to convince farmers that their proposition wasn’t too good to be true. In Laos, a farmer’s buffalo is their bank account. Each is worth 12 million kip (US$1,200), roughly the average annual salary.

During their information sessions with farmers, Rachel described the pushback: “You mean you want me to give you my buffalo? You're going to take my buffalo to your farm. You're going to feed her. You're going to vaccinate her. You're going to take care of her. You're going to help when she has a baby, you're going to take care of the baby. You're going to vaccinate the baby. Then when you start to milk her, you're going to pay me for the milk. And then you're going to give me back my buffalo and the baby and money. What's wrong with you people?”

Enter Somlit, the chief of Thinkeo Village. He understood how this venture could become a new income stream for his community and was willing to rent them his buffalo for the six-month milking season. Farmers who came to the new dairy could see how well his buffalo was doing. “Look at how fat they are compared to your buffalo,” Rachel would say on these tours, “because these buffalo are getting fed a proper diet and your buffalo are scratching for food because it's the dry season.”

3. Work with the community, not just for them.

The original plan did not include housing the buffalo during milking season or becoming part of a national breeding initiative. They were just supposed to pay the farmers for the milk. But these programs were necessary to gain the community’s trust. It wasn’t uncommon for NGOs and charities to show up for a few years then move on to the next thing.

The farm’s investment in a breeding program tipped farmers over. “Outside of our farm, 50% of the calves die before six months. Inside our farm it's less than 5%. That's a big difference when this is your bank account we're talking about. It took about 18 months for the babies to turn around, moms to get pregnant again with better genetics, go off, have another baby. And farmers finally started saying, you know what? This is a really good deal. I'm getting in on it.”

They’ve also started training Village Champions to teach farther-flung villages how to use and care for their buffalo. They can then sell their milk to the dairy, plus it helps with another challenge: child malnutrition. In Laos, 44% of children are chronically malnourished before the age of two. By age five, it's almost 50%.

Rachel explains: “All they need to do is milk their buffalo, take 500ml of milk and put it in the rice cook pot in the morning. They will effectively pasteurize it by boiling it. And they will impart the nutrition from the milk to the rice to their entire families. So they can work on the malnourishment problem within their villages before anybody ever gets truly very sick.”

Working with the Department of Health, children are weighed and measured on a regular basis. As the kids grow, they’ll be able to track how this milk is contributing to better nutrition.

4. Nurture multiple opportunities

Alongside supplying dairy products to the luxury hotels and restaurants in Luang Prabang and Vientiane, the farm welcomes tourists for a day out petting buffalo and eating lemongrass-flavored ice cream. Until the pandemic hit, Rachel says, “We were looking at becoming sustainable all-in and possibly making a little bit of a profit.”

Laos closed its borders early to fight COVID-19, and the country has done well, with only 45 cases and no deaths. Tourism revenue, however, has evaporated. They’ve been able to keep the farm open and retain staff on slightly lower salaries, and are focused on growing non-tourism revenue.

One of these opportunities is supplying cheese to Japan. It’s a relationship that started three years ago when a buyer visited the farm looking for new products to bring to Japanese consumers. The dairy has shipped 300 kilograms of cheese to Tokyo over the last two years, and their cheese will be presented at the massive FOODEX trade show in Chiba, Japan in March 2021.

With the help of volunteer organization Crossfields, their website has been translated into Japanese and their product will be promoted on Japanese social media.

“We're in the process of trying to raise funds to expand equipment. If we can get that up and running where we're delivering two tons of cheese to Japan every month, that's 163 buffalo that need milking every month.”

5. Have somebody in your corner

Rachel describes her co-founder Susie Martin as “a superhero in business terms.” A seasoned executive, Susie lived in Burma and Jakarta then moved to Singapore to run the Asia-Pacific business for Servcorp. And she shared Rachel’s cheese obsession -- she even named her daughter Brie.

While Rachel is in charge of production and marketing, Susie leads business development and fundraising, and is adept at navigating bureaucracy. Ask her for tips on getting a governor’s signature on a permit. She had to get nine.

Rachel had Susie to lean on in the dark days of failed mozzarella. “I would try and make cheese, and it would fail, and I would cry, and Susie would say, ‘Well, we can sell it as mozzarella crumble. It still tastes good. It'll be great in a salad,’ which of course would make me laugh. And then I'd try again.”

This all started with a personal need for cheese. With creativity, grit and resilience, it has scaled as a purpose-driven enterprise. Rachel’s view: “You have to have somebody in your corner, like Susie, who can see outside the box and see how you can make something work when it seems like everybody's trying to tear it down, and find another way to keep going.”

Get updates on Laos Buffalo Dairy through their website, newsletter, Facebook and Instagram.

As you read this, you might be thinking, “My friend so-and-so would enjoy this.” Click the orange button below for 8 different ways to share Foolish Careers with your friend.Upcoming interviews:

An indie filmmaker’s diverse revenue streams

Using LinkedIn like a human: tips from a music composer

Previous stories:

Creating a Netflix-worthy comic book despite a demanding day job

Giving up rock-and-roll journalism to recalibrate a writing career

Was this forwarded to you? To get a new story each week and connect with the Foolish community, subscribe here:

Featured Fools

Where we highlight the things creators say and do. I want to feature as many of you as possible, so introduce yourself and any projects in this thread.

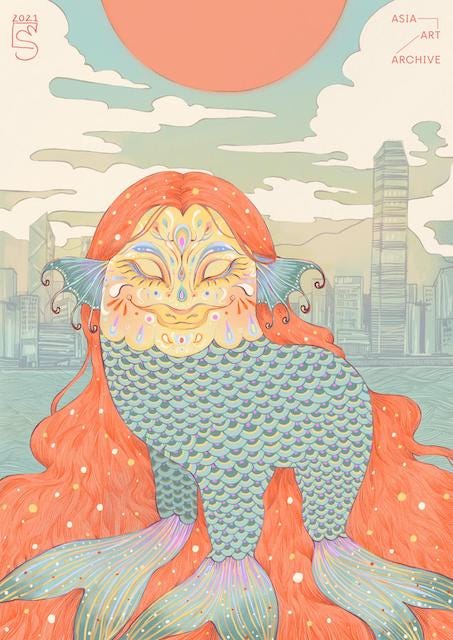

Thank you to reader Alexandra Seno for this Chinese New Year greeting, a special downloadable and printable amabie (pronounced ah-mah-bee-ey). Alex is an arts administrator with Asia Art Archive and an art critic. The amabie was reimagined by Charlotte Mui, a member of the AAA library team who has an art practice outside of the office.

Why the amabie, Alex?

This Japanese supernatural being emerged from the sea near Kumamoto [in the 19th century] and predicted a pandemic, instructing people to draw and pass around its likeness to defend against disease, and promising good harvests to come.

To us in Hong Kong at AAA, it also resembles Lo Ting, the mythical part-human, part-fish ancestor to the first settlers of our hometown. Long-lost magical maritime cousins, perhaps?

Please accept this heartfelt wish for positive energy for the year ahead, and as a timeless celebration of the healing power of art.

The amabie has gone viral in Japan. The Health Ministry uses it in COVID-19 communications, and people are sharing images online, on fabric, and in food.

Quick Poll: What do you think of the newsletter?

🔥 It's great! ~ 👍🏼 It's good. ~ 😐 Meh. ~ 🤷🏻♀️ I've heard this all before.

Late on reading this, but what a fabulous story! Well-researched, well told and thoroughly illuminating!

Loving this article Timi. How we can all become a big cheese in our communities with some creativity, persistence, and a clever idea ....